CONDITIONAL PARDON

or monetary reward?

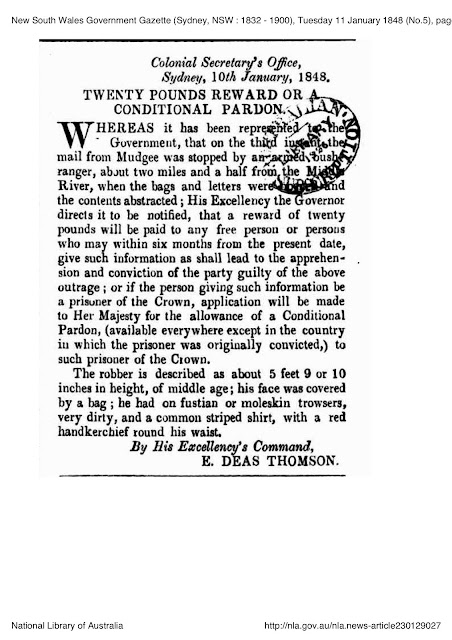

New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW : 1832 - 1900), Tuesday 11 January 1848 (No.5) National Library of Australia http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article230129027

*****

What do we discover from this simple notice?

There was a mail robbery.. whereby mail from Mudgee was 'opened and contents abstracted'...

There were two forms of rewards offered.. either twenty pounds or a conditional pardon... which meant if a convict gave information leading to the capture of a robber, he/she would be free except in the country in which he/she was originally convicted.

We also have a description of the robber 'as about 5 feet 9 or 10 inches in height, of middle age: his face was covered by a bag; ' etc.

Seems that's all, except for one thing..

E. DEAS. THOMSON..

Just an official from the Colonial Secretary's Office... or was he?

Meet Sir Edward Deas Thompson

courtesy of

also known as Deas Thomson, or Edward

He was born in Edinburgh, Mid-Lothian, Scotland..1 Jun 1800. He was both a public servant and a parliamentarian, he lived in Scotland, England and the United States as well as Canada, then the West Indies.. before taking up a position as clerk to the Executive and Legislative Councils in New South Wales for the princely sum of 600 pounds a year. He went on to have a long and illustrious career in the public service, and was honoured with a knighthood in 1874.

- Own work

You can read about his life in much more detail here

There is always more to the story...Now you've 'met' Sir Edward, you will notice his name on so many notices.

Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1875), Monday 12 December 1853, page 3

Edward Deas THOMSON.

The following rather happy portraiture of the Honour-able the Colonial Secretary is from the pen of a gentle- man who is present a member of the Thomson Testimonial Committee.

The honourable the Colonial Secretary for New South Wales is acknowledged, on all hands to possess remarkable business talents.

That is to say:

Mr. Thomson performs the office of Colonial Secretary, which is a somewhat laborious one, to the entire satisfaction of his superiors at home; to his own satisfaction, also, without doubt ; to the satisfaction of that portion of the colonists who are dependent upon him ; and, as far as the routine of his duties goes, to the satisfaction even of his political opponents.

No one will deny to the honourable gentleman the praise due to his assiduous industry to his extensive information on matters concerning his office-to his invincible urbanity to his good natured endurance of all the avanirs necessarily attaching to the position which he occupies as working head of the government.

In Council, Mr. Thomson is never taken aback. If by chance any very startling motion is brought forward in the House a rare occurrence, be it known the Colonial Secretary may feel surprise at his own unpreparedness, but he never shows it. On the contrary, he rises with his usual self-possession : and, advancing to the table and leaning on both his hands, turns his head towards the Speaker, and says, " I do not rise, Sir, to oppose the motion of the honourable member," exactly in the same tone and with the same self-confident nonchalance which he would exhibit on making a motion of course.

You never feel afraid for him. There is no halting or hesitation in his movements nor, although his eloquence be but of the smallest, does he ever seem at a loss for words. He strings his sentences together with a very unnecessary number of ums and ahs but the machine does not stop ; the wheel never wants greasing. Edward Deas Thomson has always something to say.

The honourable the Colonial Secretary for New South Wales is acknowledged, on all hands to possess remarkable business talents.

That is to say:

Mr. Thomson performs the office of Colonial Secretary, which is a somewhat laborious one, to the entire satisfaction of his superiors at home; to his own satisfaction, also, without doubt ; to the satisfaction of that portion of the colonists who are dependent upon him ; and, as far as the routine of his duties goes, to the satisfaction even of his political opponents.

No one will deny to the honourable gentleman the praise due to his assiduous industry to his extensive information on matters concerning his office-to his invincible urbanity to his good natured endurance of all the avanirs necessarily attaching to the position which he occupies as working head of the government.

In Council, Mr. Thomson is never taken aback. If by chance any very startling motion is brought forward in the House a rare occurrence, be it known the Colonial Secretary may feel surprise at his own unpreparedness, but he never shows it. On the contrary, he rises with his usual self-possession : and, advancing to the table and leaning on both his hands, turns his head towards the Speaker, and says, " I do not rise, Sir, to oppose the motion of the honourable member," exactly in the same tone and with the same self-confident nonchalance which he would exhibit on making a motion of course.

You never feel afraid for him. There is no halting or hesitation in his movements nor, although his eloquence be but of the smallest, does he ever seem at a loss for words. He strings his sentences together with a very unnecessary number of ums and ahs but the machine does not stop ; the wheel never wants greasing. Edward Deas Thomson has always something to say.

What that something is may very fairly be questioned. Nine times out of ten, no one knows, except the Colonial Secretary himself, and, perchance, his parliamentary aid-de-camp, Mr. Michael Fitzpatrick, who, though not a member of the House, takes his seat as regularly at Mr. Thomson's left hand, as the clock strikes three in

the afternoon.

To statesmanship, Mr. Thomson has not the shadow of a claim. I have never heard him give expression to a single original idea. He has no genius; he has no individuality; he has no will of his own. The mandates of his masters are to him law and gospel. He carries them out as a matter of course; and if he is defeated on any one point, he cares nothing about it; knowing very well that he will probably win all the others ; and that if not, he is not responsible. Defeat will not affect him ; however it may embarrass those who give him "instruc-tions." In short, he takes things coolly. As to oratory, he possesses nothing of the sort. He never spoke warmly, I should think, in his life. There is no spirit in his voice, his action, or his intonation. When he speaks, the House listens because he is Colonial Secretary ; when he sits down, the house rejoices that his "observations" are concluded.

Mr. Wentworth always calls his honourable friend the "Colonial Seccatore:" whether intentionally or not it it would be hard to say ; but never man deserved better such a sobriquet.

In personal appearance Mr. Thomson strikingly resembles the average of Downing-street second fiddles. When he wears the "Windsor" on state occasions, one is apt to enquire what right he has to that tall, top-heavy, white and red feather which grows with such pretension out of the apex of his plain cocked hat; and also, why his sword is not worn at the side, as swords ought to be, instead of encumbering the action of his leg by being, brought "amidships." But these are trifles.

In conclusion, if I were deliberately asked to say who

Mr. Thomson most reminds me of, I should unhesitatingly reply, and others would reply with me-Olly Gammon, Esquire. .

the afternoon.

To statesmanship, Mr. Thomson has not the shadow of a claim. I have never heard him give expression to a single original idea. He has no genius; he has no individuality; he has no will of his own. The mandates of his masters are to him law and gospel. He carries them out as a matter of course; and if he is defeated on any one point, he cares nothing about it; knowing very well that he will probably win all the others ; and that if not, he is not responsible. Defeat will not affect him ; however it may embarrass those who give him "instruc-tions." In short, he takes things coolly. As to oratory, he possesses nothing of the sort. He never spoke warmly, I should think, in his life. There is no spirit in his voice, his action, or his intonation. When he speaks, the House listens because he is Colonial Secretary ; when he sits down, the house rejoices that his "observations" are concluded.

Mr. Wentworth always calls his honourable friend the "Colonial Seccatore:" whether intentionally or not it it would be hard to say ; but never man deserved better such a sobriquet.

In personal appearance Mr. Thomson strikingly resembles the average of Downing-street second fiddles. When he wears the "Windsor" on state occasions, one is apt to enquire what right he has to that tall, top-heavy, white and red feather which grows with such pretension out of the apex of his plain cocked hat; and also, why his sword is not worn at the side, as swords ought to be, instead of encumbering the action of his leg by being, brought "amidships." But these are trifles.

In conclusion, if I were deliberately asked to say who

Mr. Thomson most reminds me of, I should unhesitatingly reply, and others would reply with me-Olly Gammon, Esquire. .

*****

Another offer of a Conditional Pardon but only five pounds reward this time, apparently the demise of a valuable horse wasn't considered quite as important as the mail.

NUMEROUS CONDITIONAL PARDONS

New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW : 1832 - 1900), Friday 28 January 1848 (No.12) National Library of Australia http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article230129270

They are not in any particular order, so you will just have to read through to see if you recognise any names. It's always worth looking, even if you don't know of any convicts in your family.

Quite often, some families glossed over the fact that they had a convict ancestor, though in these times, we who are descended from Australian Royalty, are quite happy to claim them.

Further Reading:

No comments:

Post a Comment

I welcome your comments. All will be moderated before publication.